The Domesday Book

The Book of Winchester

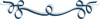

The Book of Winchester was the Domesday Book compiled by officials of William the Conqueror on his orders and published c1086.

Domesday BookBy courtesy of the National Archives, Kew, London.

Winchester was the Norman capital as it had been of the Saxons, so The Treasury was there at that time. The Book, an account of all the holdings of England down to the plough, the ox and the ass, was an extremely important document. It told of the wealth of the country, who held that wealth and where it was. William the Conqueror had an up to date account of his own land holdings and tenure holdings, that of his minions and the very few native English who had survived the Norman land grab. It had to be held in a secure and handy place, The Treasury was the answer. The chest in which it was kept still exists in the National Archives at Kew in London.

To start with The Book had no name and so where it was became its name – The Book of Winchester.

People then were no different to now, who likes taxation. They resented the intrusion into their private affairs, but could do nothing about it. One wonders what would happen if such a survey was carried out today!

There was no appeal as to its contents – hence the term The Domesday Book, It was called that very quickly by the population.

How it all happened

The ”Anglo Saxon Chronicle”, which recorded the annals of the Anglo Saxon times and continued into the Norman period, describes how it all happened. The Book started life after King William I had a “very deep conversation with his council” about the land and its population. The King then sent out his royal officials to find out. They did and recorded everything about everybody and the land on which they lived.

From these documents the King knew exactly how much he could tax his subjects and how much military might he could summon in the case of a war.

William the Conqueror

Photograph in the National Portrait Gallery

Under the Saxon Kings, England was a well ordered and quite prosperous country. The land was divided into shires (counties), and the shires into hundreds. A hundred is an old Saxon term but was used for many centuries after the Norman Conquest. A useful small administrative division to local level. It was from Saxon times the amount of land needed to sustain one hundred homesteads. An easy system to adminster.

It is not surprising the Conqueror wanted the country. He not only conquered it in no small measure, but stated that he owned it. From henceforth all land was held from the King. He then installed Normans into the properties evicting the Anglo Saxons. A few were able to buy back their properties but not those who opposed this upstart, illegal King as they thought of him. It became a Norman aristocracy.

Christmas 1085, the King was in Gloucester, a city and area close to Wales where the King had had his problems. The Welsh were not keen on Norman rule. To solve these he had set up marcher counties along the Welsh border with castles under Norman Barons for defence. Even so these problems did persist for a century, long after William had passed away.

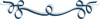

Edward the Confessor depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry

Also Gloucester had historic connections with the Godwine family. William had defeated King Harold Godwineson at the Battle of Hastings. Arguably it is probable that discussion of ownership of land and loyalty to the crown came up and discussion went further as to what taxes had been paid under Edward the Confessor. Certainly William needed to know the answers, not just in Gloucester but throughout his kingdom.

The Welsh were not the only ones not keen on Norman rule, William the Conqueror did not get it all his own way without a lot of fighting.

Eadgar Aetheling, the last of the Saxon heirs, with the northern earls and the Danes were a force to be reckoned with. William marched north and laid the country to waste literally. Those that were not killed, starved. The Danes left with the usual bribe of gold and the earls fled to Scotland and King Malcolm. Eadgar married King Malcolm's sister, Margaret. William marched into Scotland and made King Malcolm swear fealty.

William had made his point, he was not going to stand for revolt. However his scorched earth policy in the north and towards Wales meant that his Treasury were going to lose out on taxation, no one to pay the taxes!

Resistence by the English was fierce defending their homes and land. In the southwest of the country it was very hard. William had not been averse to using the same scorched earth policy conquering the south west. A young Hereward the Wake was to the fore in these fights.

Hereward the Wake

The last rebellion to William was led by Hereward the Wake among others in East Anglia. Hereward is said to be the son of Leofric, Earl of Mercia and Lady Godiva of Coventry fame, although it is not certain. There are other possible parents including new research that states he may have been a Dane, which puts a completely different slant on things including maybe bringing England back into the Danish fold! That he was born in Lincolnshire is probably known, but most of his story is a mixture of fact and fiction. He was a brave, determined and perhaps hot headed young man. If his mother was Lady Godiva one can see where he got his bravery and determination from! Perhaps also his hot headiness!

Courteenhall, in Northamptonshire, the home of the descendants of Hereward the Wake

Photo in the public domain

Hereward did not like the fact that the Normans had taken over his father's estates and killed his brother. Hereward had been abroad at the time. Swein Estrithson. King of the Danes landed again in England, despite his bribe from William after the Harrying of the North. This time the Danish King landed on the Isle of Ely near Cambridge. A story of loyalty, betrayal and resistance followed. Earl Morcar, brother of King Harold, who had been active in the northern rebellion and Hereward joined the King of the Danes on the Isle.

Hereward was worried about the treasures in Peterborough Cathedral and led a raid there to save them from the Norman's clutches. Hereward shared the gold with the Danes and they as usual went home – a Viking tradition of centuries.

The Normans tried to raid the Isle of Eley, but they did not succeed. The Abbot of Ely Abbey was caught in the middle. He was a Saxon, but worried about the Normans and what they might do to his Abbey, not unnaturally given William's reputation. The Abbot told the Normans how to get to the rebels and the Earl of Morcar was captured. William pardoned him on his death as he pardoned other of his prisoners.

Hereward and his men got away and lived as outlaws in the fens. Here fact and fiction merge. He is mixed up with Robin Hood in stories, myths and legends. William eventually had to come to terms with Hereward and it is said his lands can be found in the Domesday Book. (Search by the author did not find a reference.) Other sources say he was killed.

The Book of Winchester

The Book of Winchester is in actual fact two books. ”Little Domesday” covers the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex in great detail. Although only three counties this book is larger than the main one. Again historic connections. Those revolts in the Fens had made their mark. William wanted to know all about those rebels.

”Great Domesday” covered most of the rest of the country. A large part of the north was only wasteland after the wars and this shows. Durham had its own taxation to the Bishop of Durham.

Both London and Winchester were not included in The Book. The main cities of the Kingdom William would have known about anyway, particularly Winchester as Edward the Confessor had had a survey done there. London was a crowded urban area and the collection of information would have been more difficult those days.

How it was done

The time frame of compilation is mind boggling for the era. The request by the King and the planning was in 1085 and the books with all their detailed information were published in 1086. Officials had collected that information from all over the land.

Communications are not what they are today, nor was technology. The counties had a visitation by the royal officials to the shire court. Results were reported in The Hundreds. That would have made it easier to adminster and record. Still there was the logistics of travel. Then it was all written out - by hand!

Imagine the scene – would make a great film – Royal Officials in their grandeur riding to the shires with their entourage, the massive weight of the King's decree as their legal authorisation. Taking over the imposing shire halls with power to call everyone to count. Intimidating. Nerve wracking. Their word would have been law. There was no appeal then or later.

The landowners were Norman, they knew or guessed what the penalty for not obeying would have been. They wanted to keep their new found lands and great wealth. Opposing the King was not the right way to go about that!

Perhaps the East Anglian Book was compiled first and shown to the King who was then so pleased with it he wanted the rest in a hurry! Pressure from the top. Physically he was a pretty big guy and charismatic too. The second book has a more abbreviated format – rushed? Maybe why!

It is possible that it was all recorded but not completely finished in 1086 as some sources say that King William 1 did not live to see it. He died from injuries after falling off his horse in France at the Siege of Mantes in 1087.

Henry II

Picture in the public domain

Gloucester came into its own by the middle of the next century when Henry II (William's great grandson) gave the city its first charter. That gave the burgesses (freemen) of that city the same rights as London and Winchester citzens. Quite a deal.

It was Henry II who moved his Treasury from Winchester to Westminster in London. Like all the other treasures and documents, The Book of Winchester, moved too, although The Book had moved around with the court for easy access before. The Treasury became the Exchequer later.

Henry II had styled himself King of England instead of the King of the English used by his Norman predecessors. Henry II was very much a legal eagle like his grandfather Henry I.

Printed Editions

Quite a few printed editions of the Doomsday or Domesday Book have been made along with the development of printing and technology. Antiquarians wanted better access to the volumes and in 1773 the government decided to go ahead. Ten years later saw its publication as two books.

The Domesday Book is a complicated work set up in counties, but otherwise difficult to just dip in. As there were no indexes to the first publication they came out in 1811.

A great deal of interest and research followed. Antiquarians and historians were avid for more information about the country after the Conquest. What was life like, who was who, what happened.

A further interesting volume came out in 1816. It was indexed from the start. Set up in four sections. Two of these areas cover the regions where rebellion had taken place. Further details had been wanted by the monarchy, by then William's descendants, to make sure taxes were paid, military duty done and above all that rebellion did not break out again. Two were areas not covered by the original survey.

The Exon Domesday was a land and tax register set up for the Domesday Book and covered the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire. Would have been a very useful addition for research, although it is not a complete record. The only surviving copy is in the Library of Exeter Cathedral.

The Inquisito Eliensis covers Eley Abbey

Liber Winton (Winton is another name for Winchester) is a later survey of Winchester. It was in fact a combination of two surveys. The first was in the reign of Edward the Confessor, but there are no copies of that in existence now. The second was done by Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester. He was also known as Henry of Winchester and the man responsible also for St Cross Hospital and almshouses in the town.

The Bolden Buke covers the Bishopric of Durham. This area had not been included in the Domesday Book as the system of taxation was direct to the Bishop. This later survey was ordered by the Bishop and is a century later than the Domesday Book but similar in content.

A Photocopier!

The late 1800's saw photography come into its own. We take it for granted now, but then it was a bit magical although the pinhole camera had been known for a long time. A cheaper and easier way to copy the Domesday Book it was thought. Original thoughts for the photocopier!

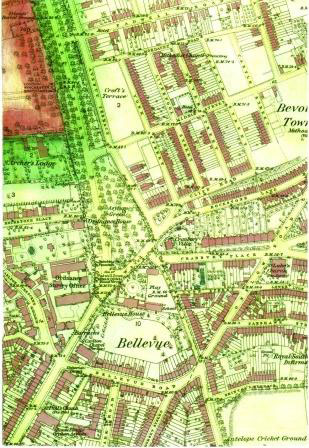

1865 Ordnance Survey Map Southampton made by the Photozincography method.

Picture in the public domain

Ordnance Survey maps were already in use by this time. The Director General of that organisation.Colonel Henry James had already used the photozincographic method for producing inexpensive survey maps. He suggested to the Prime Minister, in answer to a query regarding the copying of old documents from the Chancellor of the Exchequer, that this method should be used in that context too. He was asked to reproduce the Cornwall part of the Domesday Book to show how this could be done. (The Exchequer was the successor of the Treasury of earlier times)

Photozincography is a method by which documents could be copied by transferring the new magic photographs in one of several ways. In this case a photo of a page of the Domesday Book. Then this photo went on to zinc or even stone or a copper plate with a waxed surface. It could then be engraved. Faster and cheaper than printing.

Between 1861 and 1863 the Domesday Book was published successfully this way by the government, county by county. Pretty exciting stuff then and made the Domesday Book more available to historians and antiquarians.

Modern editions

The first of these editions was the ”Great Domesday” published in both Latin and English by Phillimore & Company Ltd in Hampshire during the 1970's. Seeing the text in both languages sets up an ambient feel for the times. A feast for academics.

The Alecto Editions were collectors copies. Very special, expensive editions indeed made during the 1980's and early 90's. There were three of these editions.

(Alecto is part of Greek mytholgy and the word translates as “implacable or unceasing anger”. Does this reflect the Domesday name of the book?)

The startlingly named ”Penny Edition”. What was being tried was to replicate as far as possible the original without the exhorbitant cost of using parchment. It was still going to cost a mint and did! They printed the book on paper made from cotton to resemble parchment, then bound it in oak sheets. A silver penny from the reign of William the Conqueror and a specially made one from the late Queen Elizabeth were set in the sheets. Hence the name The Penny Edition. There were only 250 every printed. Something really special.

William I silver penny

Copying old manuscripts is a specialised job and has to be done very carefully to preseve the original. Apparently the camera used to produce the ”The Penny Edition” was the size of a small car!

The Millenium produced a myriad of responses and among these was a new edition of the Domesday Book known of course as the "Millenium Edition". This one was bound in calf skin – beautiful soft leather – mimicking the two original volumes. Together with those high quality volumes came other wonderful items. There was a volume of very useful indices to start with. A translation into English of the original Latin to allow it to be read by non Latin readers which would be most of us. Then a delightful historical connection, a box set of the Ordnance Survey maps with an overlay of the Domesday places. An incredible edition, albeit highly expensive. There were only 450 copies made.

The last of these editions was the "Library Edition". This edition needed to be able to stand the test of time and usage. This was the one to be accessed by ordinary folk in a library. The same paper as the other two versions was used but there was a linen cover.

In 2002 along came a very affordable edition made by none other than the famous Penguin publishers not surprisingly. It does follow the original Domesday Book, but is only written as an English text and is one book for both volumes. It appeared first as a hard back and then later as a paper back. The first time the Domesday Book was available to purchase by the ordinary interested person. Certainly increased the fascination.

Online Edition

Now there is an online edition. We can all obtain a PDF of the places we are interested in, for a fee of course. Published by the National Archives at Kew in London, it can be found here.

Published as a family history resource, it is that. It is more though. It chronicles all the places in the country at the time of the survey, so many of them go well back into history before that. It shows the wealth of the individual and the country. What the landscape must have been like to accommodate the various agricultural and industrial practices. The complex of the social way of life and so much more. To most of us we look to see the place we were born or lived for many years.

Britain's finest treasure.

Other pages that may be of interest

Return from Domesday Book to Home

Or you may prefer to browse some more, please do, you will find navigation buttons above on the left.

Useful Information

Domesday Book

Would you love to know about the place where you are living, or a place you know well, in 1086? You can!!!

Domesday-Book-Complete-Translation-Classics

Perhaps you might like to own your own copy of The Domesday Book? Well

why not. This is the The Penguin Classic, The Domesday Book in English.

The Domesday Quest: In search of the Roots of England

Research, facts, speculation backed up by what he has found. Michael Wood has brought this interesting subject to life in his own way. Readable and quite fascinating. A new slant on this tricky subject. Recommended.

Hereward the Wake, 'Last of the English'. Charles Kingsley

A truly great story, a classic. Historical fiction about one of the heroes of England, Hereward the Wake.

You might be interested in this book about the history of the Wake family. It can be obtained from the The Courteenhall Estate priced at £25 including postage and packing.